RADIO INTERVIEW

http://www.drrus.com?section=ll&id=61

By Joshua M. Greene

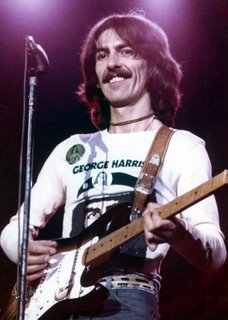

George Harrison taught me something about spiritual health. This was in 1970—the year his song “My Sweet Lord” became the most successful single by any of the Beatles. George had been recording an album of Sanskrit prayers at Apple Studios, a project that reflected his appreciation for chanting as part of a complete daily spiritual program. I was a student of Krishna yoga visiting London at the time. As former organist in a college band, my good fortune was to be invited to chant some of the prayers and play harmonium on the album.

During rehearsals, George’s appreciation for the simplicity of India’s devotional songs affected us all. Nonetheless, from bad habit I began playing an embellished riff during an introductory solo. George looked at me with an impish grin and raised his eyebrows. “Really?” he seemed to be saying. Realizing my mistake, I quickly went back to the basic melody line, but the point had been made. Prayer should shine a spotlight not on us but on the Divine. Spiritual health begins by distancing ourselves from such self-centeredness. I’m still working to free myself from ego. For George, it came naturally.

We were never close friends, but even people who barely knew him noted his natural humility. “None of us is God, really,” he’d say, “just God’s servants.” To cultivate his deep devotion to Krishna (the Sanskrit name for God in human form), he woke up early and performed yoga postures for half an hour or so. Then he’d sit quietly with prayer beads before an altar that he kept on the mantle over a large fireplace in his home Friar Park, a few miles west of London. The altar contained small images of various deities and pictures of spiritual teachers whom he admired including Swami Vivekananda, Paramahansa Yogananda, and Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. For someone who lived at the apex of superstardom, his humility before more advanced souls was stunning. He told us that his worldly success, first as a Beatle and then in his phenomenal solo career, proved to him there was some greater magic out there. Success, he said, had given him the freedom and the courage to seek it out. That freedom, he said, was a privilege given to him after millions of births and deaths in the material world. He felt a responsibility to engage what God had given him wisely, for the benefit of others.

“If I don’t use this opportunity,” he told us, “then I’ve wasted my life, haven’t I?”

George was always careful to focus on his chanting, since he accepted the Vedic (traditional Indic) teachings that say God and God’s name are not different. To chant a sacred mantra is consequently to be in the presence of the Divine. While chanting, George sat up straight and listened to the sound of each word as he chanted on a string of wooden prayer beads called a japa-mala. If he allowed his mind to wander, it would change the quality of his prayer. He would produce sound but not divinity, fulfill a ritual but not evoke love. So he paid attention. Cares over business or tensions with friends might have distracted him from time to time, but as far as possible he put all thoughts aside and focused on hearing the sound of each word of the mantra, reaching deep inside to nurture his devotion and to sense God’s presence through sacred sound.

He would use different mantras, but the one he favored most was the Krishna mantra: Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare, Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. Chanting Krishna’s names steadied his mind. He felt purified of anger and greed when he chanted. Beyond wanting that peace for himself, he wanted to share what he’d learned with people who had no knowledge of spiritual life. That was his intent behind recording songs such as “My Sweet Lord,” which contained the Krishna mantra sung by the Edwin Hawkin Singers. Producing spiritual records was George’s way of giving back something for all that he had received. The world would acknowledge that gift or not; that was out of his hands. But he wanted to see that as many people as possible heard the chanting.

George adhered to other principles of healthy spiritual life. He was strictly vegetarian, since he felt it contradictory to honor life in its many forms and still sanction animal slaughter. His favorite dish was dahl, a lentil soup that, when mixed with rice, forms a perfect protein and is an ideal meat substitute. Living the celebrity life made it difficult for him to give up other habits, such as alcohol and cigarettes. Still, as far possible, he kept company with people who did live clean lives and who shared his beliefs. He had his musical friends and he had his spiritual friends, and he liked to keep the two worlds separate.

In his later years, communing with the natural world was a vital part of George’s formula for spiritual health. A stream ran through the grounds of his home in Friar Park, and morning wind rustled the hemlocks and oaks that grew there in abundance. Entering the final years of his life, George felt God’s presence in nature, in trees and gardens and the simple miracles of tilling the earth, planting jasmine bushes, freeing a magnolia tree from wild brambles, and nursing abused ground back to beauty. He had seen people worshiping nature in India where they called the earth God’s “Universal Form.” Trees were the hairs on that divine form. Mountains and hills were the bones, clouds the head, rivers the blood flowing through the veins. Gardening from that vantage point took on holy dimensions, as though caressing God’s body.

In his early 50s, George was attacked by a deranged man who broke into his home late on night. George sustained multiple stab wounds. A short time later, he underwent an operation for cancer. The body was deteriorating, but his consciousness remained strong and healthy thanks to daily spiritual practices. Friends listening to him sing against such odds thought it about the bravest thing they had ever heard.

George planted 400 maple trees during the final year of his life, and when he strolled around the garden he would pick up a flower or leaf whose unique shape he admired. “I think he saw in that garden an affirmation that life goes on,” said Michael Palin. “That seemed to give him great pleasure in his final days. It was almost as though the body might be weakening, but everything around him was an affirmation of life and the continuity of life.”

When friends came to visit, George would remind them to take time to live every moment to its fullest. He would ramble on about plants and flowers and hug his friends for minutes on end, not wanting them to leave before knowing how much he loved them. In their eyes he glowed with a truth that has faded in the burning fires of a world at war: that the worth of a person dwells inside, in something eternal and pure regardless of karma or politics or religious beliefs.

Even a lifetime of dedication to healthy practices cannot reverse karmic effects from previous lives. Whether it was from cigarettes or more remote causes, George passed away from the effects of cancer in November 2001. For those who were there, it was not a sad moment but a glorious passage of his soul out of the material body and back to the spiritual world.

The people of India have a tremendous spiritual strength, which I don’t think is found elsewhere. The spirit of the people, the beauty, the goodness—that’s what I’ve been trying to learn about.

—George Harrison, 1966

From 1966, when he first heard an album of Ravi Shankar playing ragas, to his death from cancer thirty-five years later at age fifty-eight, George Harrison was a lover of India and an advocate of India’s Vedic (devotional) culture.

As a fellow student of A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, founder-acharya (teacher-by-example) of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, it always astonished me to see how this world-renowned artist distanced himself from stardom to better cultivate his inner self. How many celebrities have ever done that? His dedication meant even more since he wasn’t just any celebrity. He was a Beatle. In the 1960s, my generation viewed the Beatles not just as the most successful pop group in history but as Western sadhus, wise souls in tune with deeper secrets of the universe. George first visited India in 1966, and within a few years he became a dedicated mantra chanter, vegetarian, and spokesperson for bhakti or devotional practices. If these disciplines were okay with him, a generation of young people around the globe was inclined to at least give it a try.

In those days, the impression most Americans had of Hinduism derived from books distorted by British missionary prejudice. By publicly declaring his commitment to yoga, meditation, karma, dharma, reincarnation, and other concepts identified with India, George helped reverse nearly three hundred years of anti-Hindu ignorance and bias. Even most impressive was the depth of his commitment, for which he was prepared to risk his career and his credibility. On one occasion in 1970, when George visited the Radha Krishna Temple in London where I was studying, he told us that his worldly success, first as a Beatle and then in his phenomenal solo career, proved to him there was some greater magic out there. Success, he said, had given him the freedom and the courage to seek it out. That freedom, he said, was a privilege given to him after millions of births and deaths in the material world and he felt a responsibility to engage what God had given him wisely, for the benefit of others.

“If I don’t use this opportunity,” he told us, “then I’ve wasted my life, haven’t I?”

As a boy, George had been an indifferent student, but once he discovered spiritual India he was rarely without a book in his hands. Among his favorites were Swami Vivekananda’s Raja Yoga, Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi, and Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada’s Science of Self-Realization. What these books revealed about Indic spiritual wisdom amazed him. Unlike institutional religions that barely tolerate one another, here was a worldview that encompassed everyone and everything. All living beings are eternal souls, part and parcel of God, the texts declared. Our job is to manifest that divinity. This, the Hindu tradition said, is sanatana-dharma, the eternal religion, which dwells in all beings. “Through Hinduism I feel a better person,” he told a reporter. “I just get happier and happier.”

The other Beatles, John, Paul, and Ringo, were his closest friends, and in 1968 he induced them to join him and his then wife, model Patty Boyd, on a retreat to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s ashram in Rishikesh. The group arrived in Delhi at three o’clock one morning in February 1968, and by noon their hired cars were weaving down Rishikesh’s dusty streets crowded with cows and bullock carts. They got out and climbed a path leading to a bluff above the river’s eastern bank. Before them, stone huts and wooden bungalows mushroomed out from groves of teak and guava trees. Looking out over the bluff, the group traced the Ganges River flowing from a source high in the mountains.

The Beatles’ days in Rishikesh consisted of a casual breakfast, morning meditation classes until lunch, leisure time in the afternoons, and sometimes as many as three more hours of meditation in the evenings. George and his friends found their creative energies heightened in the peaceful atmosphere of the retreat: in Rishikesh, the Beatles composed more than forty songs. Many were recorded on the White Album, and others would appear on their final LP Abbey Road. Still, George encouraged his friends to make best use of their time in India, not by writing songs but by practicing yoga and meditation. This is a land of yogis and saints, he reminded them, and people hundreds of years old. “There’s one somewhere around,” he said, “who was born before Christ—and is still living now” and then went looking, climbing paths that snaked high into the mountains.

George’s commitment to communing with these mystic beings impressed the other Beatles. “The way George is going,” John said with admiration, “he’ll be flying a magic carpet by the time he’s forty.”

#

On return to London, George met Krishna devotees who had come to open a temple. George identified with the young Americans, people his own age who had rejected materialism for higher ground. In their company, George began to chant the Hare Krishna mantra daily and to read the Bhagavad-gita.

George held India’s sacred texts in high regard, but his realizations were experiential rather than academic. In his post Beatles songs, he only occasionally referred to philosophical terms and preferred writing simple, sing-along lyrics. In “Living In The Material World” (1973), for instance, his declared “Senses never gratified/Only swelling like a tide/That could drown me in the material world.” The lines offer a terse rendering of several verses from Gita chapter two, which describe “While contemplating the objects of the senses, a person develops attachment for them, and from such attachment lust develops…then anger…then delusion…then bewilderment of memory…then loss of intelligence…[after which] one falls down again into the material pool.”

Inspired by the Gita’s injunction that the divine energy animating all life has no material name, George referred to himself as a “spirit soul” rather than a Hindu. Perhaps it was because of this deep respect for God’s universality that he never took formal initiation into any one tradition. “The guru-shishya (teacher-disciple) relationship is an exceptionally powerful one,” he wrote in Ravi Shankar’s autobiography Raga Mala. “In order to gain the benefits of the received wisdom of the ages, the student must yield completely to the demands of the guru in a submission of the ego [and] must accept without question what he is taught.” If he’d learned anything as a Beatle it was to question authority, and pledging himself exclusively to one teacher, it seems, was a step he never felt prepared to take.

Still, George appreciated those who had sincerely dedicated themselves to God, and as often as his busy life allowed, he spent time with his fellow chanters. On several occasions, after a day of recording, he invited us to his home in Friar Park north of London. We’d arrive at Henley-on-Thames, a quiet town thirty-six miles west of London, and George and Patty would greet us at the gates of their sprawling property with a wave and a smile. When devotees visited, George flew an Om flag from the tower of his gothic manor.

Signs of George’s devotion to yoga and meditation filled his home. Incense sweetened the air. A small altar sat on the mantle of the fireplace. Pictures of favorite teachers and paintings of deities from India’s scriptures decorated the walls: Lakshmi, the Goddess of Fortune; elephant-headed Ganesh; Krishna playing with his friends in the cowherd village of Vrindavan. George found Indian theology exciting and sensual, filled with meditative music, tasty food, fabulous stories of eternal worlds, and all the satisfactions a newcomer to the spiritual journey could ever hope to find.

But George’s spiritual journey was not an easy one. His wife Patty left him, in large measure because his commitment to God grew stronger than his commitment to their partnership. Fans derided him for taking his faith onstage and exhorting them to “Chant Krishna! Jesus! Buddha!” when it was rock and roll they wanted. The press was occasionally cruel in its judgment of his post Beatles music. And for a while, some bad habits from his rocker days—in particular alcohol and drugs—returned to haunt him.

Salvation from the material world can come in many forms. For George, struggling with depression after the Dark Horse debacle, it came in the form of Olivia Arias, a fellow yoga practitioner who nursed him back to health and later became his loving wife. It came in the form of their son, Dhani, a gentle, talented boy who in time became George’s closest friend.

In later years, George retreated from his pop celebrity into the life of a humble gardener. He took great pleasure in tilling the earth, in planting jasmine bushes, in freeing a magnolia tree from wild brambles, and bringing his neglected Friar Park grounds back to a state of beauty. In India, he had seen people worshiping nature. The Gita calls the earth God’s “Universal Form.” Trees are the hairs on that divine form, mountains and hills are its bones, clouds form the head, and rivers are the blood flowing through its veins. Gardening from that vantage point takes on holy dimensions, a caressing of God’s body.

Gardening, caring for his family, and meditating became the focus of his life. “The best thing anyone can give to humanity is God consciousness,” he told Mukunda Goswami, a devotee friend, in 1986. “But first you have to concentrate on your own spiritual advancement. So in a sense, we have to become selfish to become selfless.”

In April 1996, he began work on an album of traditional Indian songs and mantras with Ravi Shankar. The album was released in 1997. George considered Chants Of India one of his most important works, as it allowed listeners to “turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream, and listen to something that has its roots in the transcendental…beyond intellect. If you let yourself be free…it can have a positive effect.”

George never stopped making music or trying to put a spiritual message out into the world. But these callings seemed less urgent to him in his later years than they had as a young man. He once described himself as someone who had climbed to the top of the material world, then looked over to find that there was much more on the other side. There, on the other side of the material mountain, was the call of his eternal self and his relationship with the Divine. As he approach death, with his missionary years behind him, that vision became all that mattered. “Now I understand about ninety-year-old people who feel like teenagers,” he said less than a year before his death. “The soul in the body is there at birth and there at death. The only change is the bodily condition.”

George’s life started in music and ended in music. In Los Angeles, surrounded by family and friends and the chanting of God’s holy names, his soul left its body on November 29—only a few weeks after the tragedy of 9/11. For those of us who had been inspired by his example, it was impossible to avoid seeing these two events in macabre orbit around one another: the terrible consequences of turning away from the light, and the miracles that can come when we put the light of spirit at the center of our lives.

In August 1966, a reporter had asked George to describe his personal goal. “To do as well as I can do,” he replied, “whatever I attempt, and someday to die with a peaceful mind.” He was twenty-three years old when he set that goal for himself. He never gave it up.

“You know, I read a letter from him to his mother that he wrote when he was twenty-four,” his son Dhani said. “He was on tour or someplace when he wrote it. And it basically says, ‘I want to be self-realized. I want to find God. I’m not interested in material things, this world, fame—I’m going for the real goal. And I hope you don’t worry about me, mum.’ And he wrote that when he was twenty-four! And that was basically the philosophy that he had up until the day he died. He was just going for it right from an early age—the big goal.”

When the world around him seemed to be falling apart, yoga helped George Harrison overcome depression and dependency. If being a Beatle had taught him anything, it was to always go with the best, and going with yoga to overcome a dark time in his life was no exception.

George’s stress level had been building for years. From 1961 to 1966, as a member of the world’s most successful pop group, he made seven tours of the U.K., three of America, one of Europe, and two around the world. The Beatles played more than 1,400 club dates, often as many as three in a day, in addition to 53 radio shows, 35 television programs, and slogged their way through more recording sessions than any band in music history. By the time he 23 years old, George had already lived a lifetime of anxiety and tension.

George’s connection with yoga began when he heard a recording of ragas and sitar music in 1966. The sound struck him as familiar, “not intellectually,” he explained, “but emotionally” as though returning to some place he already knew. Ragas, which have the power to evoke deep spiritual emotion in listeners, led him to inquire about the philosophy behind Indian music—and that led to a trip to Kashmir later that year to study sitar and astanga-yoga. Each morning, from the deck of his wooden houseboat overlooking the Himalayas, he breathed in bracing mountain air and practiced sitar, his eyes shut, his fingers familiarizing themselves with notes along the instrument’s long wooden neck. Then he would do yoga asanas, sitting in a half-lotus position, breathing in slowing and breathing out the sacred sound AUM. When his exercises ended, he read books on self-realization by Swami Vivekananda and Paramahansa Yogananda, and in the peace and calm of an ancient land the young seeker discovered teachings that would permanently change the course of his life.

In 1970 the Beatles dissolved, and George launched a solo career with songs about his spiritual search that skyrocketed him to the top of the pop charts. His single “My Sweet Lord” featured the Edwin Hawkin Singers chanting the Hare Krishna mantra to organist Billy Preston’s gospel chords. It was an inspired combination—Hindu revivalism, the pop equivalent of interfaith prayer. By the end of January 1971, “My Sweet Lord” was selling more than 30,000 copies a day with total sales in America alone surpassing the two million mark.

That same year, in the U.K. his first solo album All Things Must Pass earned more than ten million pounds, and for a while it seemed George Harrison could do no wrong. In 1971, with his work solidly in the number one spot on charts around the world, he mounted the first charity rock concert in history, the Concert for Bangla Desh, which eventually raised several million dollars for victims of the war-torn nation. The concert also earned George the reputation of an activist willing to put his spiritual beliefs on the line for a good cause.

The debacle of his career came two years later. George’s third solo album Dark Horse garnered only mediocre reviews, and on the album’s promotional tour things went from bad to worse. George opened each show with Ravi Shankar and a troupe of Indian musicians playing a lengthy program of Indian music that had fans yawning and restless. When he came on to perform the second half, George’s constant exhortations to “Chant Krishna! Christ! Krishna! Christ! Allah! Buddha!” added to their unease. Where was Beatle George? People had come expecting at least a few Beatles memories but George refused to be pulled back into that material persona.

“Give the people a couple of old songs,” Ravi entreated him. “It’s okay.”

After a performance in California’s Long Beach Arena, George found himself wandering alone through the stands, remembering a quote from Mahatma Gandhi: We should create and preserve the image of our choice. The image of his choice was not Beatle George. His life belonged to God now, and playing the old hits would have felt hypocritical. How could he live with himself if he reinforced people’s illusory attachment to nostalgic tunes and images?

“Every show was probably hard for him,” said violinist L. Subramaniam. “My impression was that George wasn’t just looking to popularize Indian music but also a path of spirituality. But the press really wasn’t always sympathetic. Anyone else under that kind of pressure would have said, ‘Okay, I’m calling it off.’ But he took the risk of going on. Why did he do it? I always had the feeling someone very special was occupying that body.”

Why did he do it? Perhaps because George understood that somewhere along the way humanity had suffered a loss of spiritual vision, and no one else in entertainment had the courage to say so. If fortune had given him the resources for reaching wide publics, how could he avoid the responsibility that came with spiritual knowledge? George put his career and credibility on the line to send a message out into a spiritually impoverished world.

But now he was confronting the greatest disappointments of his life. His wife had left him, in large measure because of his preoccupation with spiritual pursuits. The Beatles had broken up. And now he was grappling with the devastating realization that most people simply didn’t care to hear about Krishna or yoga or getting liberated from birth and death. The world wanted rock’n’roll. The world preferred him as a Beatle.

Despite his public protestations to the contrary, some part of him cared deeply that the world was rejecting him and he went into a depression. His smoking and drinking increased and he developed a severe case of hepatitis from the “brandy and all the other naughty things that fly around” as he later described his habits at that time. Drugs had first entered his life at age seventeen when the Beatles played Hamburg and amphetamines were an easily acquired stimulant for all-night sessions. His drug use had gone up and down in the intervening years. Now it was back.

The ensuing despair forced him to recognize, “Jesus, I’ve got to do something here.” And that was when he remembered his yoga practices. “I had forgotten totally that that’s what it was all about—to release the stress out of your system,” he told journalist Al Aronowitz. He resumed daily yoga practice, daily chanting of the Krishna mantra on beads, and started paying closer attention to diet and exercise. He took Ayurvedic cures and concentrated on saving himself before trying to save the world. “In a sense,” he told a devotee friend in later years, “you have to become selfish in order to become selfless.”

He compared his need for daily meditation to a drinker’s need to attend an Alcoholics Anonymous program. Meditation was something that had become necessary “to keep myself focused and keep the buoyancy, the energy, and also to realize that all this stuff that’s going on is just bull. It’s hard to be able to not let that get next to you.”

Resuming yoga practice restored control and energy to George’s life. Daily practice freed him from harmful habits and inspired a repertoire of memorable post-Beatles songs. In yoga, as in music, the quiet Beatle achieved liberation from the material world.